East vs. West

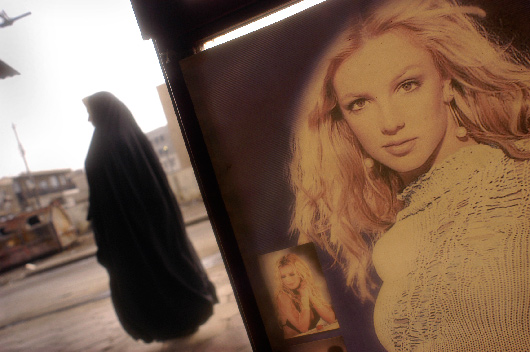

An Iraqi woman walks past a music store near the Baghdad University of Technology on Al Sinaa Street in Baghdad, Iraq. The store, which sold bootleg CDs, was decorated with posters of Britney Spears and other American rock stars.

I saw relatively few women wearing an abaya in Baghdad in 2003, prior to the U.S. invasion. This comes as a surprise to most people; most U.S. citizens (it seems) assume that prior to the current war, Iraqi women possessed few rights; they assume Iraqis were forced to wear the burqa, were hidden away at home. Maybe under lock and key.

The country has made somewhat of a move in that direction, but that’s happened partly as a result of the invasion, and the destruction of Sadaam Hussein’s secular government.

I believe that it would be accurate to say that Iraqi women had a lower social status than U.S. women in 2003, but the situation has worsened, not improved. Prior to the U.S. invasion, UNICEF assessed the welfare of women and children in Iraq, and determined that compared to other nations in the Middle East, Iraqi society was relatively progressive. Although Sadaam Hussein ruled as a dictator, he ruled as a secular dictator, meaning he had no discernible objections to women serving in professional roles such as attorneys or physicians.

The rise of fundamentalist movements in Iraq has been said to “fill a power vacuum.” The tangible dimension of this ‘vacuum’ is that by late summer 2003, women told me they were afraid to be seen driving. Rumors (and by rumor I mean “a story being told without linking it to verifiable evidence”) were circulating about women being dragged onto the street and beaten, if they were caught driving. I’m not sure the stories were true. Women believed them.

The fear was real enough. They opened their purses to help me understand—showing me kitchen knives and handguns. They meant to fight back.

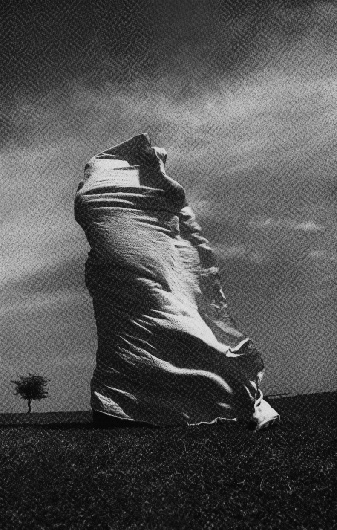

By late summer, they were afraid to not cover their hair, or faces. Afraid to go to work—if work meant being a surgeon, the CEO of a company ... anything that strongly challenged the belief that ‘a woman’s place is in the home, cleaning, and bearing children.’ Numerous organizations have attempted to document the impact of the war on the rights of women and children; Human Rights Watch, for example, addresses concerns about sex trafficking post invasion, the impact on literacy and health care, increased murder and domestic abuse rates, and torture. And while these transgressions are far more tragic, immediate and dramatic problems than the imposition of the burqa or abaya, the cultural shift itself—dressing not for success, but survival—is a sign of the cancer that grows its tendrils through everything.

I didn’t conduct an ‘abaya statistical survey,’ but it seemed the times were changing. The Baghdad that I knew in January and February was one in which women seemed intent on convincing the community that they were Republicans, and this was Southern California. They’d sometimes dress provocatively, as ‘provocative’ might defined by J.C. Penny’s. Kind of Assistant Deputy Undersecretary of Sexy. (Which is not to say that anyone is “more

free” because he or she dresses more provocatively.)

But by late September, they were deep in mourning, and dressed for it. And it’s even blacker now. Black as a veil on both body and spirit, settling over the country. It’s more dangerous to look “modern” and “Western,” where prior to the invasion, looking modern and Western was a point of pride, particularly for young people. To do so now is to paint oneself as a target.

And now that I’ve said all these things that seem to imply that I have some personal objection to women wearing an abaya or burqa, let’s be clear—I don’t. My understanding is that the Koran never mentions it specifically, and that the prophet Mohammed’s wives did not cover their heads. The directive to cover one’s head, or face, is an outgrowth of the Sharia—the body of laws that purport to interpret and amplify the Koran.

Some women, and some men, see the burqa as a matter of personal conviction. How I feel, to be precise, is that it would be better if it were a choice, not a life preserver. We have interesting (shall we say) practices in the West, which include the wearing of a suit jacket and tie at the office, apparently because we’ve all agreed that meetings run more efficiently if we all believe we’re being slowly choked to death. High heels seem like a Western attempt to cripple women, while Americans condemn customs such as Chinese foot binding.

While I might complain about the absurd male ritual of tie-wearing, I’m sure I’d view it fondly, sing its praises, if I thought that leaving my neck bare would earn me a severe beating or death.

I’ve spoken with Muslim women at the University of Baghdad College of Arts who said they wore the burqa at college because they were sick of being hounded by men; they wanted to focus on their studies. They’d found in the ‘law’ a provision that could finally protect them ... from the men who wrote it. (Note: the terms abaya, burka and niqab are used interchangeably in U.S. culture, but that’s not necessarily accurate. For more on the history and cultural meaning of ‘the covering,’ see Wikipedia.