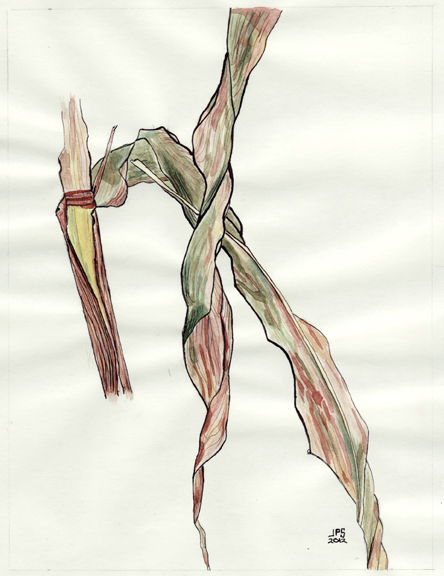

Corndoggle

Corndoggle

by Joel Preston Smith

BioSteel® is a product created from an animal-animal transgenic combination. Scientists at Nexia Biotechnologies … isolated the gene for silk protein from a spider capable of spinning silk fibers—one of the strongest yet most resilient substances known—and inserted it in the genome of a goat’s egg prior to fertilization. When the transgenic female goats matured, they produced milk containing the protein from which spider silk is made. The fiber artificially created from this silk protein has several potentially valuable uses, such as making lightweight, strong, yet supple bulletproof vests.

— Linda MacDonald Glenn, Ethical Issues in Genetic Engineering and Transgenics

It’s fascinating to think about a world in which a grilled goat-cheese sandwich might be tasty, but could also stop bullets. Who needs gun control if all it takes to foil a madman is a jacket patterned from impermeable curdled butter?

Fascinating, but maybe a little scary. Opponents of genetic engineering usually play the Frankenstein card—fears of organisms gone awry or run amok—or they stew over the ethics of ‘playing God,’ but here’s a closet door that hasn’t often been opened: genetic engineering’s implicit promise that rewriting the genetic code will allow us to ignore environmental concerns, or—by extension—the social contract itself. That if we can’t adapt to the world by being responsive and responsible to each other (and the world we live in) ... well, we could always just rearrange a few molecules.

Enter Monsanto and the BASF corporation. The chem giants recently co-engineered a drought-tolerant corn hybrid, by stitching a bacterial gene (termed cspB, or cold shock protein B) from Bacillus subtilis into the maize genome. Allegedly, researchers were attracted in part to B. subtilus (a bacterium found in soil and the human gut) by the fact that it possess exceptional tolerance to extremes of heat and cold, and can sometimes even survive being boiled in water. It sounds awfully, awfully messianic in a world whose temperatures are projected (by the U.S. Global Climate Change Research Program) to rise 2 to 11.5 degrees by the year 2100.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture approved DroughtGard for commercial release last December after an environmental-impact assessment concluded the GMO hybrid posed “no significant impact” to the environment, in conjunction with a 2011 study by the USDA’s Animal Plant and Health Inspection Service (APHIS; based largely on data submitted by Monsanto) that determined DroughtGard corn was not itself a pest risk to other plants. More than 10,000 acres in the Midwest, spread over 250 farms, are currently in field trials, according to Monsanto.

Or were in field trials. Supposedly, DroughtGard fried along with much of this year’s corn crop in Iowa, Nebraska, Illinois and Minnesota—the principal U.S. corn-producing states. The USDA hasn’t drawn the bottom line for the 2012 harvest, but the agency does project a 13 percent decline in corn harvest, compared with 2011 figures. Depending on who you ask, the U.S. in the midst of the worst drought in a generation, or a quarter century, or since 1960 ... In Nebraska, the first week of September saw ranchers killing cattle due to a lack of silage; the Lincoln Journal Star reported farmers were baling their corn for use as hay. The USDA has designated 1,934 counties (about 4/5ths of the continental U.S.) as “drought disaster areas.”

“It looks bad,” says Thomas E. Clemente, Ph.D., Eugene W. Price distinguished professor of biotechnology at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. Clemente notes that in order to successfully fertilize, corn has to have some water from late July to mid August. “In the Midwest,” he observes, “we haven’t had a drop of rain since June [as of Sept. 6]. One more year like this and the world is truly going to know what global hunger means.”

Neither Monsanto nor BASF have claimed publicly—but not in explicit language—that DroughtGard is a panacea for global warming. That kind of over-reaching could be better attributed to the editors of Scientific American, who reported in May of last year that DroughtGard was unique in its ability to “thrive on less water.”

Unless by ‘thrive,’ the editors meant ‘scrape by,’ or ‘become a little less crippled than its conventional peers,’ the claim shouldn’t be seen as much more than a leg-up for Monsanto’s marketing division.

Paul Thompson, Ph.D., pronounced Drought-Gard “an environmental boon,” in a Sept. 9 essay in The Wall Street Journal, adding that the transgenic crop was capable of “reducing water use.” Thompson, who serves as W. K. Kellogg Chair in Agricultural, Food and Community Ethics at the University of Toronto, refers to ‘reduced water use’ no less than five times in the essay.

The USDA seems to argue otherwise. In deregulating DroughtGard (given the designation MON 87460 in federal documents), the agency noted, “To some extent, all U.S. com varieties have been becoming more drought resistant over time ... Therefore, the impacts of a determination of nonregulated status of MON 87460 would not likely be different from the corn seed options that currently exist.”

Monsanto has made a vague assertion (in press releases and marketing materials) that DroughtGard produces “more crop per drop,” but submitted no data in its application for deregulation to back up that nebulous language.

As for DroughtGard shelling out more corn per drop of water—that would be science fiction/fantasy. The USDA’s environmental impact study (citing Monsanto’s own data) states, “Physiological evidence and recorded measures of moisture depletion strongly indicate that water use (uptake of water by the plant) is not different between MON 87460 and conventional com ...”

It’s not clear of course, the degree to which sloppy journalism and overzealous speculation—in contrast to the USDA’s findings—will help bankroll DroughtGard if it comes onto market as a commercial crop next year. Thompson, who served as a consultant for Monsanto between 2001 and 2004, sounds optimistic: “[T]he implications of DroughtGard—and other seeds reducing water use that are sure to follow—extend far beyond the fields of Iowa and Nebraska.”

Clemente notes that the Monsanto/BASF hybrid was engineered only to “broaden the window” in which corn can tolerate reduced rainfall, not live solely on sunshine and baked earth. If rains taper off in Iowa in late August, for example, enough corn might still be fertilized to sustain a profitable yield. Monsanto’s application to the USDA for deregulation of DroughtGard claims the GMO variety can cut yield losses (on average) by about 6 percent, compared with losses of up to 15 percent during moderate droughts.

A BASF press release explains it succinctly (if not a little vaguely): “In corn, cspB works by helping the plant maintain growth and development during times of inadequate water supply.”

“But that doesn’t work when you have drought like this,” Clemente observes. “You still have to have some rain. There’s nothing that’s going to save a crop in a drought like this.”

The vague language, and even the term “drought tolerant” seem to have led to a leap of faith: that despite the potential desertification of the Midwest in an overcooked climate regime, Monsanto and BASF have developed a miracle solution. In a sense, it’s a corporate gamble that fears of a bleak future will sell seeds engineered to save us from our inability to circumvent global warming.

The Union of Concerned Scientists, in a report titled High and Dry: Why Genetic Engineering is Not Solving Agriculture’s Drought Problem in a Thirsty World, noted that Monsanto’s tests “do not accurately measure the drought tolerance the gene can offer under a range of possible conditions, including droughts of varying timing, intensity, and duration, as well as varying ambient temperatures and soil conditions.”

Corn—despite its enormous global genetic variability—still flowers everywhere (assuming everywhere doesn’t include a laboratory in St. Louis, Mo.) just after the days begin to grow shorter: just after the summer solstice. If a severe drought hits just before June 21 and lasts two months or longer, there’s simply no way to overcome the fact that fertilization (which results in the development of corn kernels) requires water. And without it ... dies. The USDA notes that corn requires about 0.1 inches of rain per day prior to pollination; after the onset of pollination, that requirement increases to 0.35 inches a day.

Four consecutive days without sufficient water can, during the period in which kernels fill out, reduce yields by 40 to 50 percent. Which makes for a very narrow window indeed.

“I’m not aware of there being a definitive strategy to overcome that problem,” says Stephen Moose, Ph.D., director of the Corn Functional Genomics Lab at the University of Illinois, Urbana, “but I think conventional breeding has already done a pretty good job of building in tolerance.”

While Monsanto’s marketing materials (and the media’s misreading of the ‘promise’ behind the science) might sometimes be specious, the company can and sometimes does speak straight about the realities of DroughtGard: “With sufficient water levels, the trait performs comparably to existing seed technologies.”

Some researchers might argue that genetically engineering drought tolerance seems like a Rube Goldberg solution—if not a nefarious means of avoiding sustainable water use in agriculture. Organic farming, on the other hand, has been found to produce soils with up to 26 percent higher moisture than conventional farming methods. Agroecologist D.W. Lotter and colleagues noted, in a 2003 report in the American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, that “organic crop system[s] performed significantly better in 4 out of 5 years of moderate drought.” To reach their conclusions, the researchers studied data from the Rodale Farming Systems Trial, launched by the nonprofit Rodale Institute in Kutztown, Penn. in 1981 and still ongoing.

Lisa Richardson, executive director of the South Dakota Corn Growers Association, says this year’s corn harvest for the Rushmore State is projected to fall 45 percent below 2011 levels. “If you had a third less rainfall, maybe the [DroughtGard] stuff would work,” she notes. “But if you’ve had no water?”

Nevertheless, she (as do other farmers and scientists) remains hopeful about DroughtGard’s ability to limit crop losses in the future. “We think there’s a huge potential.”

If only Mother Nature would comply. Would let in a little rain in the new genetically engineered window. If only Monsanto (and Syngenta and others who are developing drought-resistant crops) could coax a rain dance from DNA, on or about the summer solstice next year and every year thereafter.

In the meantime, it might be wise to plan for environmental solutions to global warming and drought. Social solutions. Sustainable agriculture solutions. A contract with the planet, say, to cut more carbon emissions and fewer trees.

“Don’t worry!” Clemente grimly jokes. “There’s no such thing as global warming!”

“You cannot predict mother nature,” adds Moose. “That strategy has been tried for a while. It doesn’t work.”

END

03/20/14 | 0 Comments | Corndoggle